Znacie na pewno tzw. „Zasadę Pareto”, nie mniej warto sobie ją co jakiś czas przypominać, nim zmarnujemy kolejne pół dnia na dopieszczanie szczegółów, na które potem mało kto będzie zwracał uwagę.

Z drugiej strony w wielu konkurencjach wygrywa się o włos, o milisekundy, o przysłowiowy grosz – właśnie wszystkie te szczegóły (ostatnie 10, a może nawet ostatni 1%), o które mało komu chce się zabiegać, albo na które większości po prostu braknie już czasu, albo siły.

Sztuka więc polega na tym, by odróżniać jedne sytuacje od drugich. Wiedzieć, kiedy poprzestać na 20, a kiedy z konsekwencją zwycięzcy maratonów walczyć o ostatni, przesądzający o wyniku 1%.

I tego Wam dziś życzę! 🙂

– Sylwester Laskowski

Zapraszam do subskrypcji Newslettera oraz do udziału w szkoleniu:

Zarządzanie czasem. Jak być lepiej zorganizowanym, wydajnym i skutecznym?

PS.1. Dla niezorientowanych

Na czym polega zasada Pareto?

Zasada 20/80, czy jak niektórzy wolą 80/20, nazywana powszechnie „zasadą Pareto” (od nazwiska włoskiego ekonomisty i socjlologa markiza Vilfredo Federico Dameso Pareto), mającej szerokie zastosowanie m.in. w zarządzaniu i ekonomii.

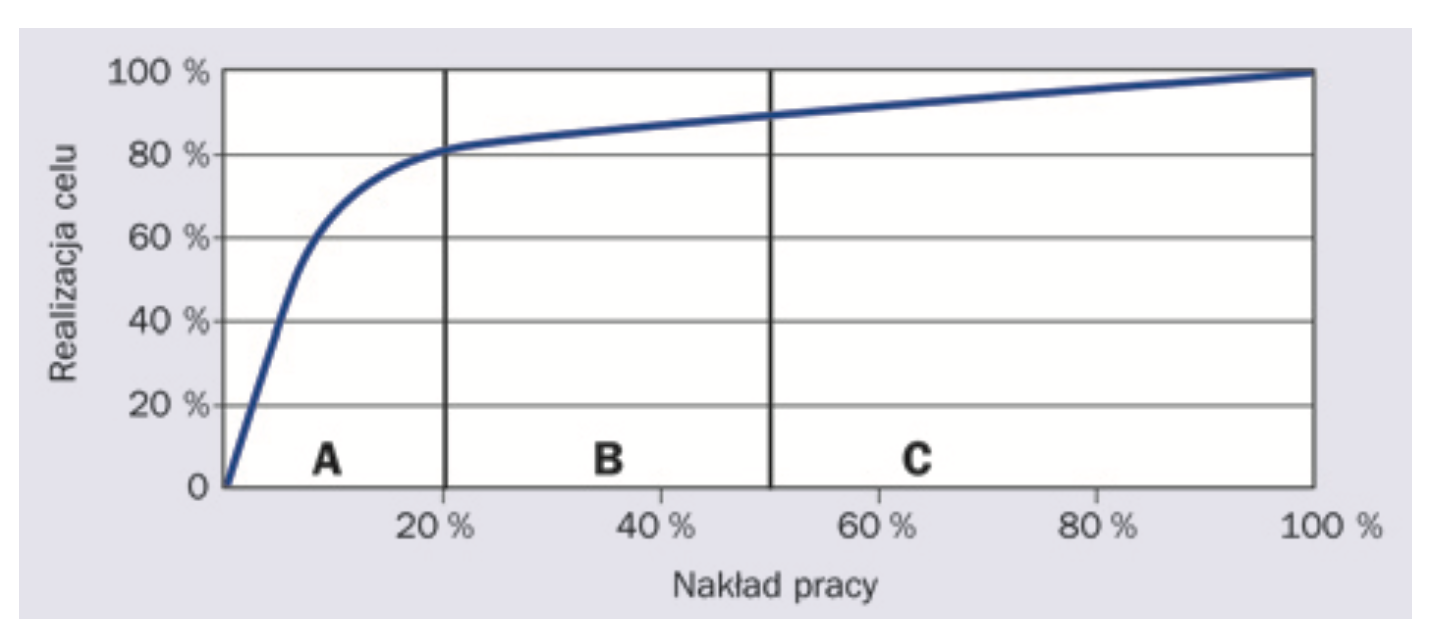

Zgodnie z tą zasadą rozkład wielu cech przyjmuje stosunek 20 do 80%. Z powyższego rysunku widzimy, że 20% nakładu pracy, koniecznego do wykonania jej w całości przynosi już 80% rezultatów. Zainwestowanie kolejnych 30% nakładu pracy, poprawia efekt zaledwie o 10%. Aby dokończyć ostatnie 10% trzeba aż 50% całego nakład pracy.

Okazuje się, że zasada ta dobrze przenosi się na wiele innych dziedzin. np. 20% klientów przynosi firmom 80% przychodów, 20% naszych spraw odpowiada za 80% ogólnej ważności tego, co się w naszym życiu dzieje, 20% wszystkiego, co mamy w ciągu dnia do zrobienia, odpowiada za 80% wyników… i tylko sęk w tym, by rozpoznać, które to te 20% 😉

Zapraszam do subskrypcji Newslettera

PS.2. Dla wnikliwych

O tym, jak Joseph Juran nieopacznie pozbawił się należnej sobie chwały

Okazuje się, że twórcą zasady Pareto jako uniwersalnego prawa nie jest wcale Vilfred Pareto, ale żyjący dużo później amerykański teoretyk zarządzania Joseph Juran.

W opubklikowanej w 1951 r książce Quality Control Handbook, uogólnił zaobserwowaną wcześniej przez wiele osób (w tym również Pareto) zasadę „kluczowych nielicznych i błahych licznych” (vital few and trivial many) na wszelkie zjawiska dotyczące alokacji zasobów.

Juran swą uogólnioną zasadę 20/80 nieopacznie nazwał „zasadą Pareto” (a właściwie podpisał jeden z rysunków w ten sposób), nawiązując do prac tego ostatniego w zakresie nierównej dystrybucji bogactw. Potem już „naukowy facebook” zrobił swoje. 😉

W opublikowanym w 1975 roku artykule „The Non-Pareto Principle; Mea Culpa”

Juran pisze tak:

„Years ago I gave the name „Pareto” to this principle of the „vital few and trivial many.” On subsequent challenge, I was forced to confess that I had mistakenly applied the wrong name to the principle. This confession changed nothing – the name „Pareto principle” has continued in force, and seems destined to become a permanent label for the phenomenon.

The matter has not stopped with my own error. On various occasions contemporary authors, when referring to the Pareto principle, have fabricated some embellishments and otherwise attributed to Vilfredo Pareto additional things which he did not do.

(…)

By the late 1940s, as a result of my courses at New York University and my seminars at American Management Association, I had recognized the principle of the „vital few and trivial many” as a true „universal,” applicable not only in numerous managerial functions but in the physical and biological worlds generally. Other investigators may well have been aware of this universal principle, but to my knowledge no one had ever before reduced it to writing.

It was during the late 1940s, when I was preparing the manuscript for Quality Control Handbook, First Edition, that I was faced squarely with the need for giving a short name to the universal. In the resulting write-up under the heading „Maldistribution of Quality Losses,” I listed numerous instances of such maldistribution as a basis for generalization. I also noted that Pareto had found wealth to be maldistributed. In addition, I showed examples of the now familiar cumulative curves, one for maldistribution of wealth and the other for maldistribution of quality losses. The caption under these curves reads „Pareto’s principle of unequal distribution applied to distribution of wealth and to distribution of quality losses.” Although the accompanying text makes clear that Pareto’s contributions specialized in the study of wealth, the caption implies that he had generalized the principle of unequal distribution into a universal. This implication is erroneous. The Pareto principle as a universal was not original with Pareto.

Where then did the universal originate? To my knowledge, the first exposition was by myself. Had I been structured along different lines, assuredly I would have called it the Juran principle. However, I was not structured that way. Yet I did need a shorthand designation, and I had no qualms about Pareto’s name. Hence the Pareto principle.

(…)

To summarize, and to set the record straight:

- Numerous men, over the centuries, have observed the existence of the phenomenon of vital few and trivial many as it applied to their local sphere of activity.

- Pareto observed this phenomenon as applied to distribution of wealth, and advanced the theory of a logarithmic law of income distribution to fit the phenomenon.

- Lorenz developed a form of cumulative curve to depict the distribution of wealth graphically.

- Juran was (seemingly) the first to identify the phenomenon of the vital few and trivial many as a „universal,” applicable to many fields.

- Juran applied the name „The Pareto Principe” to this universal. Juran also coined the phrase „vital few and trivial many” and applied the Lorenz curves to depict this Universal in graphic form.”

Cóż, rzec tylko wypada: Be careful and precise in your words. 🙂

Serdeczne dla Was!

Zapraszam do subskrypcji Newslettera oraz do udziału w szkoleniu:

Zarządzanie czasem. Jak być lepiej zorganizowanym, wydajnym i skutecznym?

– Sylwester Laskowski